By: Sommer Wagen

It’s 1982. A lanky young man joins the crowd piling out of a New York subway car. He looks furtively to his left, then to his right. He strides towards the tiled wall opposite the track, locked onto the blank black paper covering up empty advertising space. He pulls out a piece of white chalk.

He draws quickly, in full view of passersby. Some stop and watch the image develop.

In a matter of minutes, a diptych appears. Above, a simple, featureless figure snaps a stick in half, the movement and noise emphasized with short lines. A circle with a heart inside hangs in the upper left corner. Below, a figure chases another with the stick intact, Xs placed in each corner.

When he’s finished, the young man, dressed in sneakers, blue jeans and a white tank top, walks away casually, hands in his pockets. On his shirt in thick black lines is a figure in the same style, a baby crawling on all fours. Radiant lines emanate from it.

A radiant baby.

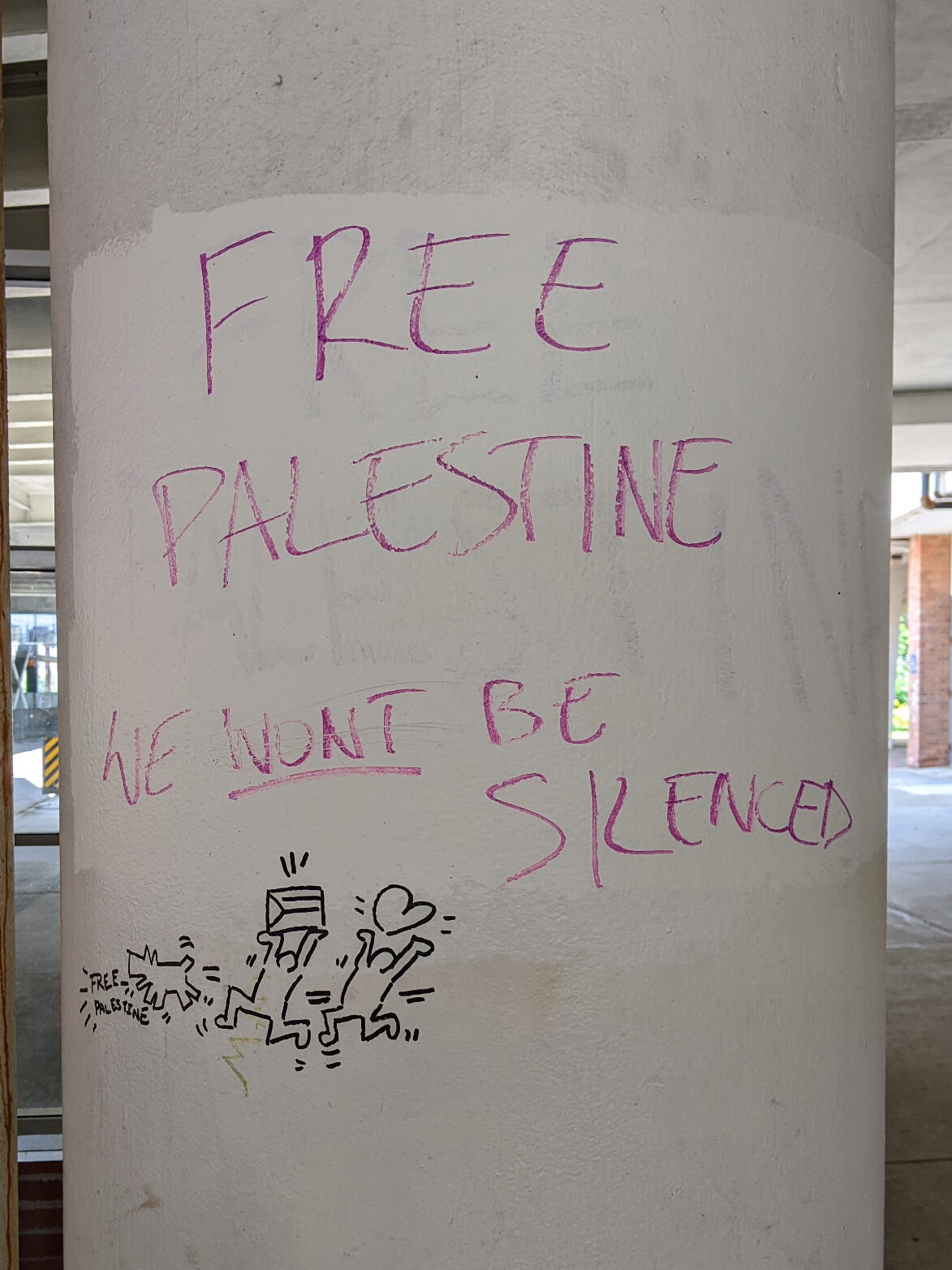

Decades later, I walk down the stairs to the lower level of the Washington Avenue bridge on the University of Minnesota campus to catch the bus home from class. I spot a message scrawled across a pillar in large purple letters:

“FREE PALESTINE. WE WON’T BE SILENCED”

Below, a blocky, barking dog drawn in black ink is chased by familiar-looking figures. One holds up the Palestinian flag, the other, a simple heart.

It’s not clear who did the image on the Washington Avenue bridge. But it’s the style of Keith Haring, the man who drew the diptych in the New York subway on CBS News more than 40 years ago, and who died 35 years ago this past February. It doesn’t feel like mere coincidence that graffiti art inspired by Haring is appearing now. In a way, the tags feel like Haring’s spirit leaving messages from beyond, reminding us from where and when it came. When you think about it, our times are hardly different from his.

A Future Primeval

It’s easy to recognize a Haring when you see one, and even if you don’t, you’ll probably feel like you’ve seen it somewhere before. The summer before I saw that first tag, the Walker Art Center in Minneapolis hosted “Keith Haring: Art is for Everybody,” the latest traveling exhibition to explore the artist’s enduring influence.

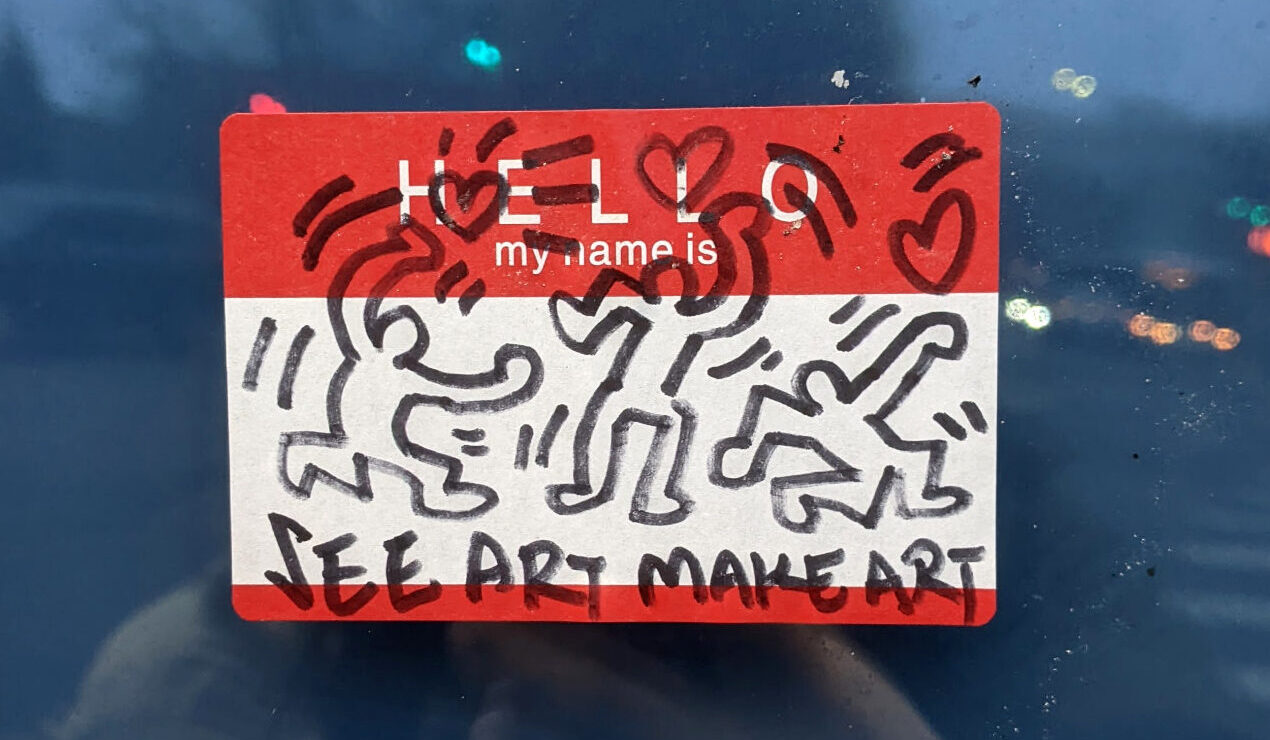

Likewise, once you’ve seen a Haring-inspired tag around campus, it’s hard not to see them everywhere — on the upper level of the Washington bridge, on the backs of bus stop signs, or hidden on a utility box outside of Coffman Memorial Union.

Recently, whoever is drawing them has been adding messages.

“Why erase art?” referencing the tags consistently being painted over.

“Please make art.”

“See art, make art.”

“¡Viva la resistencia!”

Even before his death, Haring’s work was absorbed into consumer culture, denuding it of its anti-establishment themes. When taken out of context, a bunch of wiggling, featureless figures frozen in motion are perfect for adorning $10 T-shirts from Old Navy.

But in a catalogue essay for the 1990-91 traveling Haring exhibition “Future Primeval,” Harvard psychologist and 1960s counterculture hero, Timothy Leary, places Haring’s work in the context of the “turbulent scary decade” of the 1980s.

Haring did some of his most prominent work in response to the AIDS crisis, which affected him acutely as a gay man and would later claim his life. According to the CDC, more than 100,000 deaths among AIDS patients were reported between 1981 and 1990, but no one knows how many more deaths went unreported. Journalist Randy Shilts famously argued in his 1987 book “And the Band Played On” that the Ronald Reagan administration actively ignored the epidemic due to homophobia until countless lives had been lost.

Fast forward 40 years. According to Axios, the flurry of executive orders President Donald Trump issued within his first 100 days included mandating federal recognition of only two sexes, removing the ability to change passport gender markers and removing federal funding from medical schools and hospitals that research gender-affirming care. Even the website for the Stonewall National Monument, the birthplace of the Gay Liberation Movement, which is managed by the National Parks Service, removed all mentions of transgender people, despite trans women such as Marsha P. Johnson and Sylvia Rivera leading the charge during the uprising and its aftermath.

Haring’s artwork plays a key role in queer history, and University of Minnesota students today recognize that.

“It reminds us of the AIDS crisis, and that’s it mainly for me,” said fourth-year student Kait Sisney. “It’s a reminder of how we lost so many people. We lost so much art and so much work and so much science and so much love and care.”

Still, for Sisney and other queer students, the Haring-like tags around campus are bright spots in a darkly chaotic world.

Abby Wichlacz, also in their fourth year, said they appreciate the political messages that have accompanied some of the tags.

“Especially considering the climate right now, I get the sense that I’m not the only one thinking these things and feeling a little bit lost,” they said.

The ability of Haring’s art to reach people across time gets at how Leary interpreted the phrase “Future Primeval.”

“Keith’s art spanned the history of the human spirit,” he wrote. “Keith could have jumped out of the time capsule in the paleolithic age and started drawing on cave walls and they would have understood and laughed— particularly the kids…Keith communicated in the basic global icons of our race.”

“A beautiful form of self-expression”

Perhaps unsurprisingly, the Haring tags around campus that seem to be removed the quickest are those with overt political messages. The “Free Palestine” figures that I first saw were painted over within a week.

No tag is safe from erasure, though. A larger piece that fourth-year student Stella Johnson found in a Blegen Hall bathroom that depicted figures sliding, crawling and dancing down a dragon’s unfurled tongue was also removed.

Many tags still remain, including a green figure surrounded by pro-Palestine stickers on a lamppost on Scholar’s Walk, as well as those on off-campus neighborhoods such as Southeast Como, Stadium Village and Cedar-Riverside.

Each student I interviewed objected to the tags being removed.

“I think it’s stupid,” said Sisney, a self-described “graffiti nerd.” “It’s art that we celebrate in museums and that we cherish, that people are charged money to see, but then you have a problem with someone putting it up around your campus? It’s silencing at that point.”

What’s even more ironic: Haring himself got his start in graffiti.

For some artists, graffiti is an act of reclamation.

“In a lot of senses, [it] is kind of this questioning of who gets to decide what our lives look like,” said Twin Cities graffiti artist CILA, as reported by journalist Quinn McClurg. “Why does some building owner get to decide that? So it’s this kind of flipping the script of being like, ‘No, actually, we’re going to paint on our walls.’”

Johnson pointed out how relevant this sentiment is on a college campus.

“I know the [Washington Avenue] Bridge used to have a lot of paintings and graffiti, and I think part of why they got rid of it was because it was getting ‘too political,’” she said. “But I think on a college campus you should be more free to do things like that.”

In this regard, spotting a joyously dynamic Haringesque tag on the bridge, now shrouded in a dreary anti-suicide chain link fence, feels extra special.

Johnson said that seeing the graffiti has made her want to start tagging as well.

Wichlacz, who documents the tags and other graffiti around the Twin Cities on their Tumblr blog, captioned one of their posts with a Keith Haring quote:

“I don’t think that graffiti is vandalism; I think it’s a beautiful form of self-expression.”

“Art absolutely comes from the soul”

Based on her name alone, Minneapolis thick line and pop artist Molly Haring seemed like the prime suspect for the tags around campus.

In actuality, she hadn’t even seen a picture before I showed her over a Zoom chat, but she identified the artist as a fellow “disciple of Keith.”

Molly, a trans woman, adopted the last name in homage to Keith and how his art style influenced her identity as she transitioned.

“He’s got a flow, and I feel it. I feel that flow in my body,” she said. “If a Haring is a genre of person, then I am definitely of that species.”

Molly said her goal as an artist isn’t to copy Keith’s work, but to iterate upon it, relying on simple, thick lines and shapes and bright colors while playing up the trippiness and telling her own stories.

On top of canvas paintings, Molly has also done graffiti and body paintings (which Keith also did), as well as stick-and-poke tattoos, all of which have come from the deluge of art she has produced since transitioning.

A trans woman today using Keith Haring’s art as a vessel for self-expression speaks to its powerful relevance, as well as its dynamism.

Haring once said of his art, “To define my art is to destroy the purpose of it…Nobody knows what the ultimate meaning of my work is because there is none.” Decades after his death, people are infusing his style with their own meaning. He would probably want nothing more than that.

None of the students I interviewed had an idea of who could be doing the tags. It could be a single “disciple of Keith” seeking to revive the spirit of his art, or it could be a group of them, given the breadth of their presence across campus.

“I’m kind of torn on finding out [who it is],” Wichlacz said. “It would be great to know because I want to give this person their accolades, but at the same time it’s a nice little mystery that I can think about and not associate with a person.”

In that sense, perhaps it doesn’t matter who it is. Even in death, Haring is tapping into a collective feeling that retains the power to unite.